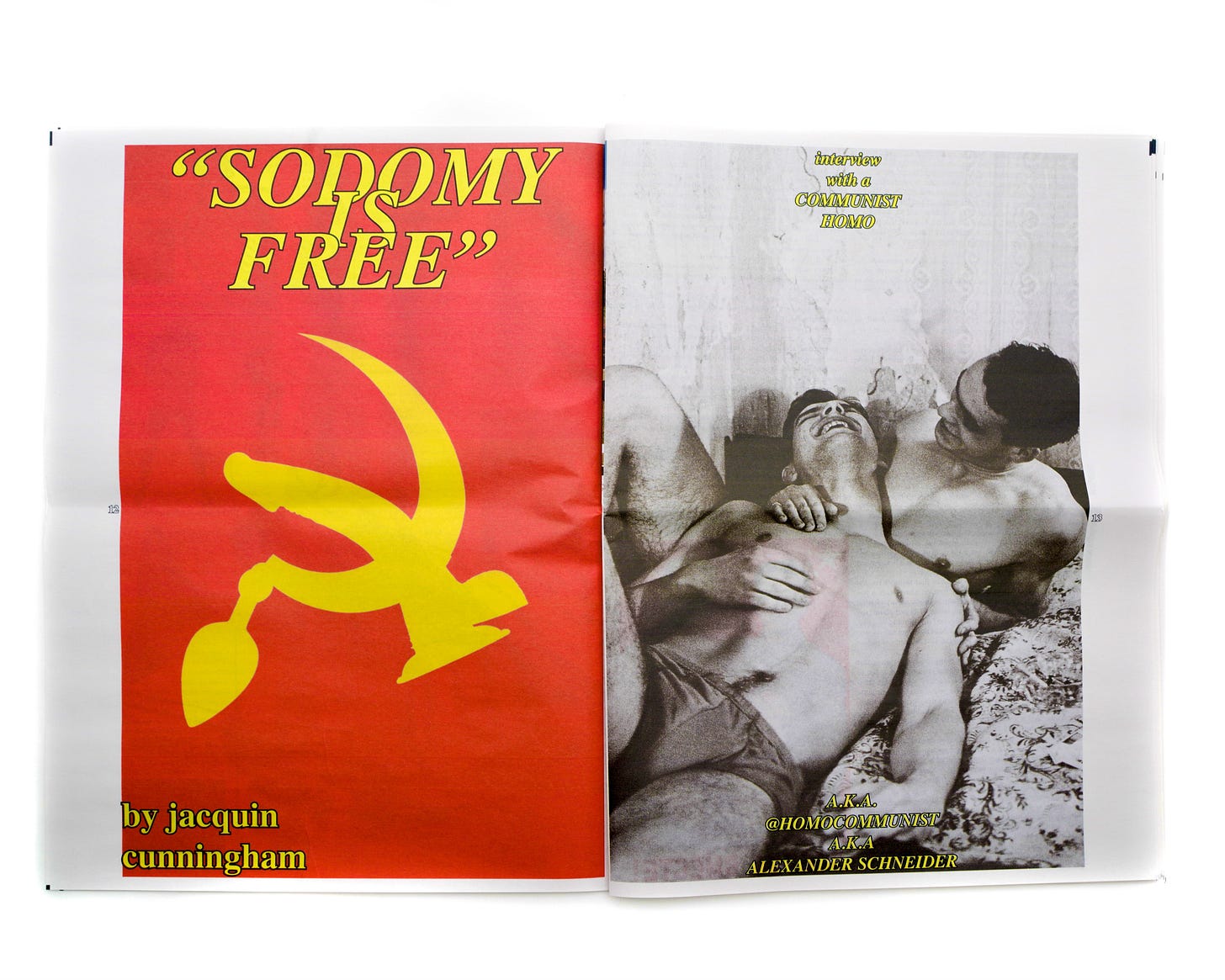

From behind the Soviet hunk in his @homocommunist profile picture, Alexander Schneider commands a following of 100 thousand comrades and counting, all waiting for the next installment of hot homo propaganda for the revolution to come. Alongside the near nudes of Andres Fux and homages to film icons like Pasolini, lies a strong political voice which Schneider uses to educate the people who came for the bods some food for thought to salivate over instead. I talked with the man behind the red and yellow curtain about what it takes to be a good homo(communist), revolutionary and how to stay sexy while you’re at it…

Pre-order your copy here!

Jacquin Cunningham: I’ve been a fan of Homocommunist for ages, so I thought now is the time to discover all the secrets to, to learn more and to talk to you. It’s so great to, to finally be able to do this as a super fan, I’ve, I’ve tried to, to colonize all my straight friends brains with homocommunist as well.

Alexander Schneider: Good. Spread the propaganda.

JC: I know you’re from New York. I read that you have family in the Eastern Bloc. So how did you begin your homocommunist journey?

AS: I think I was definitely a socialist for a very long time, even when I was like a lot younger, but I don’t really think I knew what that really meant for a while. It was just a bit shallow; but I think I did a lot of learning when I was in school, politically, but then also joined different organizations and actually meeting and doing work with radical queers and radical straights which really helped me to develop a political outlook. And that’s only gotten more radical and more gay and more communist as the time went on. But yeah, you mentioned that I do have family in the former Eastern Bloc, and my parents are from there as well and they, as a whole are not very political people. They just speak about it like how it was back in the day, like my relatives do in the non-Eastern Bloc, about how it was just different back in the day, not really giving me a political analysis and just hearing that life was normal for probably the vast majority of people.

JC: Growing up in the United States they instill in you a very anti-communist viewpoint. What was something like specific that made you like realize what you’ve been fed here was a bunch of crap?

AS: I mean there’s just so much. Definitely the pandemic era and Trump era. Maybe this isn’t even about me as much, but I’ve been seeing so many people get a bit radicalized since then because I think there was such a shake up for lack of a better word of how mainstream political discourse was going.

I think there was such a recognition that things were not going in a smooth arc of progressive history. There were a few things that I learned about that definitely shook up my view on things. For example, I just think anything I learned about, say the Eastern Bloc in the Soviet Union—and this is not to say, like, I want to go back to the past, we’re in 2024 now, you know– was about how, at the end of its existence the vast majority of people were not wanting it to be dissolved.

I think that, if anything, they wanted some reforms. But I do think the anti-communist Cold War rhetoric that is fed to us makes it seem like it was an “evil empire,” so to speak, that everyone wanted to overthrow. There were certainly legitimate problems, and certainly there were many dissidents. But I think learning about just a lot of the U.S.S.R.’s problems are actually learning that it’s just the problems of so many industrialized modern societies, including out own.

JC: When did the gay lens come in for you on that? Because I imagine it wasn’t at the beginning of your great awakening.

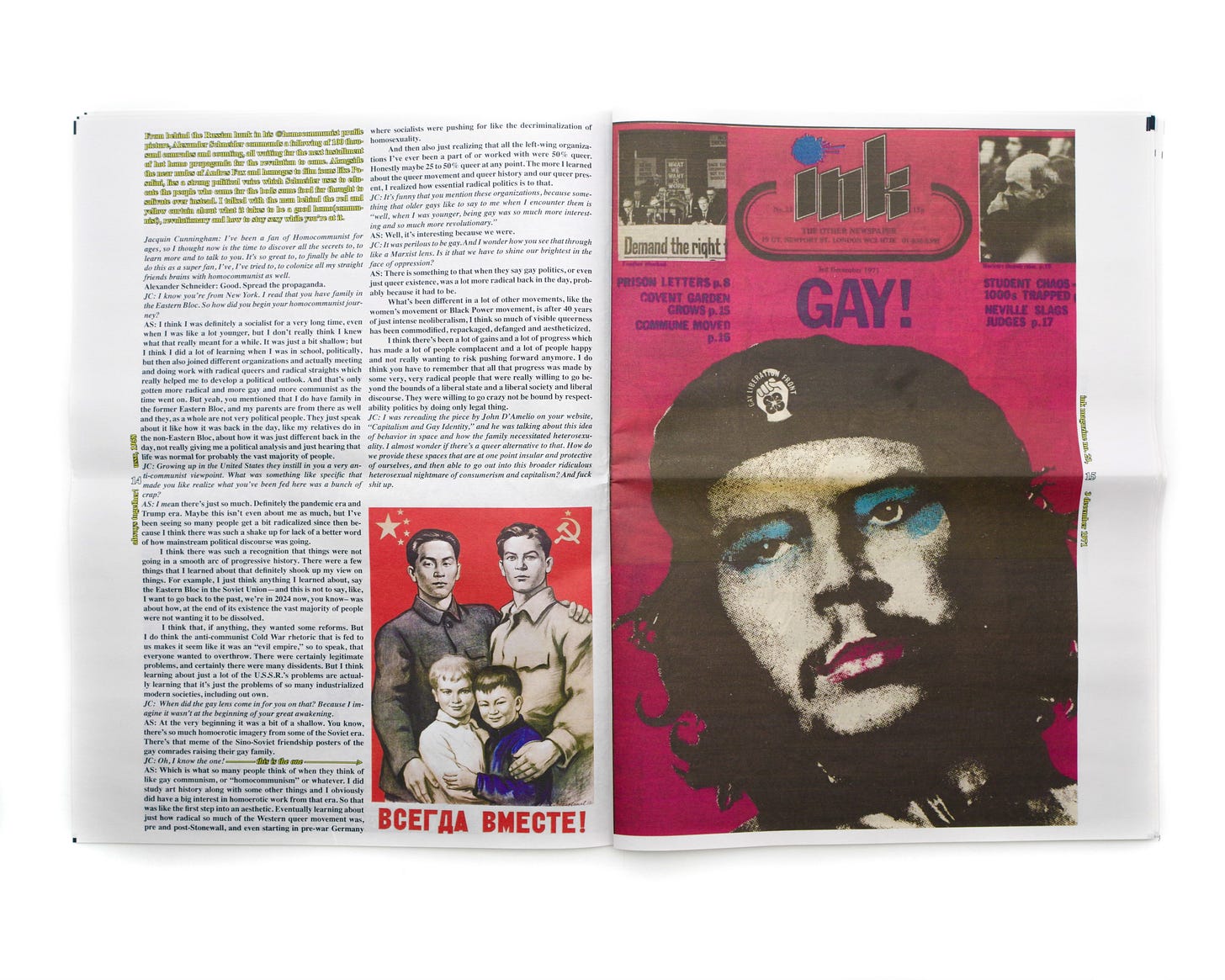

AS: At the very beginning it was a bit of a shallow. You know, there’s so much homoerotic imagery from some of the Soviet era. There’s that meme of the Sino-Soviet friendship posters of the gay comrades raising their gay family.

JC: Oh, I know the one! ––––––– this is the one –––––––––––––>

AS: Which is what so many people think of when they think of like gay communism, or “homocommunism” or whatever. I did study art history along with some other things and I obviously did have a big interest in homoerotic work from that era. So that was like the first step into an aesthetic. Eventually learning about just how radical so much of the Western queer movement was, pre and post-Stonewall, and even starting in pre-war Germany where socialists were pushing for like the decriminalization of homosexuality.

And then also just realizing that all the left-wing organizations I’ve ever been a part of or worked with were 50% queer. Honestly maybe 25 to 50% queer at any point. The more I learned about the queer movement and queer history and our queer present, I realized how essential radical politics is to that.

JC: It’s funny that you mention these organizations, because something that older gays like to say to me when I encounter them is “well, when I was younger, being gay was so much more interesting and so much more revolutionary.”

AS: Well, it’s interesting because we were.

JC: It was perilous to be gay. And I wonder how you see that through like a Marxist lens. Is it that we have to shine our brightest in the face of oppression?

AS: There is something to that when they say gay politics, or even just queer existence, was a lot more radical back in the day, probably because it had to be.

What’s been different in a lot of other movements, like the women’s movement or Black Power movement, is after 40 years of just intense neoliberalism, I think so much of visible queerness has been commodified, repackaged, defanged and aestheticized.

I think there’s been a lot of gains and a lot of progress which has made a lot of people complacent and a lot of people happy and not really wanting to risk pushing forward anymore. I do think you have to remember that all that progress was made by some very, very radical people that were really willing to go beyond the bounds of a liberal state and a liberal society and liberal discourse. They were willing to go crazy not be bound by respectability politics by doing only legal thing.

JC: I was rereading the piece by John D’Amelio on your website, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” and he was talking about this idea of behavior in space and how the family necessitated heterosexuality. I almost wonder if there’s a queer alternative to that. How do we provide these spaces that are at one point insular and protective of ourselves, and then able to go out into this broader ridiculous heterosexual nightmare of consumerism and capitalism? And fuck shit up.

AS: That is the question! How do you do that? I mean having queer spaces is so important. But then at the same time, I think it gets to the heart of this question. You don’t really want to just withdraw from the world and exist in an artificially queer space because that is not the world. There is always a bit of escapism, which I think there is a need for at points, but you can’t withdraw from the world all the time. I mean, yeah, I don’t know! how do we do it, Quin?

JC: That’s what I keep trying to figure out because I feel like there’s a group of gays, queers, et cetera, that are trying to do this within the framework of capitalism?

We have this new Fire Island garbage, where you’ve got a bunch of rich white gays who do real estate.

AS: Iconic gay gentrification, exactly.

JC: They’re just trying to buy half of Mykonos and make it some exclusive queer gated community, which what you just said is like an isolationist type thing, but also seems really ridiculous at the same time.

AS: Yeah, I do think that they’re giving it a political aesthetic. They want some cheap real estate, and they want a fun party island. Nothing wrong with having a fun party on Fire Island—whatever, right? But not the way they’re going to do it.

JC: They seem to be giving it a bit of a political flair by saying like, queers have been oppressed and now we get to go have fun and engage in gentrification.

AS: And that’s exactly the type of thing that’s not a political stance beyond the very mainstream political reality, but trapped in an economic reality of the world we live in. But with the word queer in front of it.

I posted about them, and I saw that they had—I’m not going to use the I word on myself— some influencer discount or an influencer going ahead on the wait list scheme. I was waiting what they were going to say, but they didn’t give me the check.

JC: They didn’t want the, the, the homocommunist villa, h? It’s ridiculous how they operate within the market system. And it makes me think of the way that people engage with pornography and in fairness post-collapse of the USSR. I was looking at films like “CCCP” where young men of unknown sexuality are drafted by westerners to have gay sex for money they really needed. I was wondering how you think that links to the predicament within the gay community about rampant classism.

AS: I think if we’re speaking about this, I always have to give a shout out to William E. Jones, the wonderful, fantastic artist who created “The Fall Of Communism As Seen In Gay Pornography,” and who was mining these pieces of film that we’re talking about as a way of exploring the collapse of the Eastern Bloc through porn videos made by Western producers.

I think there’s a couple of things going on there. There was this huge, cultural misunderstanding and fetishization at play with Eastern Bloc aesthetics translated through a Western gaze that they were trying to capitalize on to sell as these horny, queer, gay, Soviet soldiers. I’m the last one to talk about saying that people aren’t into that, I think I’ve discovered there’s a huge market for that. But that’s just one part of it. And then the other part of it is the real, material economic aspect that there wasn’t a market of labor available to these people. They were in dire financial straits, willing to work for so much less than Western actors would do whatever it was they needed to do. We’ll always see, in porn or in any work that opening these new labor markets in developing parts of the world allow the labor to be paid so much less and provide, us in the imperial core with the level of comfort and fun, or whatever it is they’re producing.

JC: How do you think about that within the context of your own presence online? Because as you know there’s obviously a market for this sexy gay Soviet content, and that market is inherently consumptive. I wonder how you grapple with that given the ideology behind what you’re doing.

AS: It’s how you navigate that tension between those two things in the same way that these porn actors did. There’s a balancing act and I accept any criticism anyone wants to give me. I have a lot of criticism for how to exist on Instagram and these platforms. I don’t consider @Homocommunist the end all be all how things should be done for queer communism or left-wing politics or radical politics. My account is just a little snapshot. I was just thinking about this because when I want people to see things that I post, I just need to throw up some nude men or something, because otherwise, Instagram doesn’t serve it to anyone. When I’d it just gets so many likes, so many shares, blah, blah, blah. And then everything that I fold in alongside of it gets seen by so many more eyes. That’s one of the realities of working in Instagram.

But at the same time, Instagram censors so much queer content. I just learned that like Meta is not going to be recommending political content at all to non-followers. I don’t know how real that is or when that’s supposed to be happening.

JC: It’s tough to be a gay media maven in 2024. Now, you’ll scroll and see someone, a real person, a nude woman on my screen. I think this is great! How does this exist? But at the same time, I tried to post this one completely censored image when I was doing the post with Lavender Zines and that one got taken out.

AS: Shout out to Lavender Zines. Kylle is the best! So, what happened?

JC: I posted this one (imagine full cock and balls dear reader, or turn back a few pages). For some reason, that passed muster.

AS: Wait, sorry, show me again, because … just the full cock balls. They love that.

JC: Instagram was like, fabulous. We love, but they took down the one that was someone wearing trousers and you could like see half of their ass from back. I was like, you’ve got to be kidding me! So, I’m just like what’s going on here? Because they want to simultaneously commodify the body. Like you’re saying to get, you get shares, but then does this when is it gay. And is that the problem?

AS: It’s obviously like a microcosm of daily life as a queer person. You know, there’s, there’s a fine line. I’m in my little queer corner, and I asse so are you and sometimes that breaches into a more general Instagram audience, and the straights see it and all hell breaks loose. I’ve lost my account. It’s come back. I’m always about to lose my account. I posted a 1990 or circa 1990 poster and then it just had a huge thing on it that said, I hate straights. And then I posted that it was Pride Month. It was queer history, you know, that wasn’t hate speech. They took down my account. I just emailed them, and they put it right back up. I was very confused.

JC: It seems very reactionary, which is irritating and ridiculous. But it also, I think it shows how there’s no logic to the fear that people have about queerness and how it exists online.

AS: I just think they encounter something that that shakes them up a little bit, shakes up the gender norms, shakes up the sexual norms and they don’t like it. That’s all there is to it.

JC: And I feel like a good case study for this is Andreas Fux. I really enjoyed your writing on him and I was wondering if you just talk about him and how he navigated this like new space of photographing the gay boys in the 80s and how that changed over time to then be viewed by people in East Germany, which boasted higher rates of sexual satisfaction across the board compared to their West German counterparts, which is more orgasms for women.

AS: Andreas Fux, I love his work and it’s just such a great—I don’t want to say time capsule because he is still alive and still working and is showing us photography from present day Berlin and present day German like sexual and fetish subcultures, also great—but just such a great view from East Germany and a view towards the Soviet Union or the recently dissolved Soviet Union.

He was a self-taught photographer in the 80s. I think his first photographs were in a women’s magazine. He was the one who was the first ones to be publishing male nudes in that platform in East Germany. They were pioneering nonetheless, and he was talking about how these nudes were making a political statement about his identity and adding to the political discourse rather than just an artistic discourse. He was a gay man showing a bit of gay male desire, even though I guess it was in a women’s magazine. So, you know, there’s some gender lines being blurred there. But also you said there were some higher rates of sexual satisfaction there. East Germany was like a bit of a queer pioneer, you know, I’m not saying compared to 2024, it was like a sexual playground, or like a queer wonderland.

But I do think that security and that economic security for queer people and protections from reactionaries allowed a bit of that play that Andreas had. Which I think is also a great foil for the things we saw in those videos like CCCP and Explored by William E. Jones, where there was some real exploitation going on there, and this was a bit more ambiguous, but Fux was just a much more playful and fun.

JC: It’s so interesting to think about East Germany and Berlin specifically because of course you’ve the Magnus Hirschfeld Institute there exploring transitioning and gender identity, with trans women being issued special identity passes. This is a very different experience than people had in the United States. When you look back into the queer history of the U. S., like early drag in the South and all sorts of lesbian collectives in Maine and Massachusetts, it feels so much more underground than perhaps elsewhere it was. And maybe that’s because in the Soviet Union you have these very homoerotic bits of propaganda. So, you know, maybe it doesn’t look like it’s not very every day. I just wonder what your take on how the homosexual experience, the queer experience is different as moderated under capitalism and under a socialist or communist society.

AS: It definitely was very different and a much more underground here, and I don’t want to make any statements about like queerness under capitalism. Like a very abstract communism or a very abstract capitalism. But I do think in general, in a lot of like communist societies, at least back then, but, you know, I think there was parallel in the non-communist world too. I think sexuality was a lot more private in general, and then of course like homosexuality in the 20th century, queerness, gayness, like this was sadly a new idea for many people.

Things were more underground and there weren’t these official channels for them. But then at the same time there was a lot less commercialization and commodification of it. That comes along with certain freedoms. I was reading this in a book called “States of Liberation” by Samuel Huneke, who compares and contrasts specifically gay men’s experiences in East and West Germany, and there was an account there about how any queer meeting that they were just attended in droves, and there was just so much more desire for a community. People just showed up and were ready to talk and get political and showed a lot of solidarity, and there was just a total absence of any commercialized spaces for that.

JC: I also wanted to ask you, because I think that one of the great things about @Homocommunist as a media project is the way that it engages, and you engage with media literacy and broader issues like Israel’s war in Gaza and the atrocities happening right now. But there are also a whole host of gay people who think don’t necessarily have to engage in those conversations.

AS: It may sound trite to say, but it’s always interconnected, you know these oppressions and these forces of violence. We need to be taking a stand and using whatever voice and whatever power we must stand up to literal genocide and apartheid.

But these forces are not removed from us. There are queer Palestinians who are living a horrific reality right now and have been, and that has nothing to do with them being queer. But if you want to support queer people and if you want to only be specific and only have queer politics that’s removed from other struggles, in this case you need to be speaking up for those queer people who are undergoing some really horrific things instead of withdrawing from that because of an imagined homophobia within their society in a very hypothetical way.

These struggles have so much material connections as well not just for queers, but other minorities, like in the United States, in the West, the world over. U. S. police train with the IDF. We’re selling each other weapons. We’re developing weapons for each other. And Gaza is like an experimental playground for so much killing technology. That’s only going to come back to us and come back to us if the police that are, hypothetically rounding up queer youth on the street, as they brutalize other minorities in the United States today.

There are so many direct connections that we can only fight for everyone’s liberation because otherwise they will come for us too.

JC: That’s great answer because in some ways the seeds are being planted. I think it’s so interesting to look at the way you use Soviet propaganda and look at things through propaganda because I don’t know if you saw like the Israeli queer Domino’s pizza box on Twitter?

AS: Yeah.

JC: It’s dystopian. People don’t want to admit that neoliberal imagery which is corporate and “supportive” of queers is also serving to uphold the image of, in this case, Israel’s apartheid state by saying, look at us in Tel Aviv, I can rave and eat gay pizza.; can you do that in Gaza? It’s a false justification.

AS: I do think propaganda is an interesting word, like when I was talking about violence and how so much is made invisible because it’s something we’re used to, it’s the same with ideology and with propaganda where I think, especially in the Western liberal mind, propaganda has such a specific meaning and they think of it as something that’s just unequivocally printed by the state; or it’s a poster that says this and that and it has like buff Soviet person on it and that’s propaganda.

I embrace the word propaganda because in a way, everything is propaganda. Everyone has a bias, and everyone has a message and, and I think it’s the most dangerous to think that you don’t have a point of view or that your point of view is the universalized one that is just common sense. I think it’s so important to understand where your ideas come from and what the history of those ideas are, rather than thinking that somehow you thought of them yourself and you’re a so-called thinker.

JC: Free-thinking divas roaming the land. I was going through some posts of yours and there was this one that was a take on the, the pocket system, the colored hanky system, and one of them was this idea of like, “supports the gay homeland,” and I think it’s so bizarre that that’s something that people talk about and even going back to 1980s-today in the context of the conflict in Gaza, and idea that people still want to live in this tiny bubble.

AS: But I also wonder maybe we don’t need an actual place, maybe it’s an actual place, but maybe it’s an ideal and the friends we made along the way are the gay homeland.

JC: So how does one live the ideology day to day—what are your tips and tricks for getting through the day as a certified homo(communist)?

AS: Wow. I don’t know if I even have the tips and tricks of homocommunism. I mean the gay sex is one thing, but I don’t want to suggest partying it up in the gay clubs, which is great, or fucking is like some revolutionary act in some way, it can be destabilizing some norms, you know, and that’s great, and we all should be free to be doing that, but I think at this point, that’s not really radical in itself.

But I do think to live the homocommunist way alongside that, you have to be fighting for more than that and fighting for a politics outside of queerness. Queerness is like the absence of boundaries and the absence of like a very specific imposed heterosexual and cis heterosexual system on us— and that’s something that we’re fighting for everyone to be free from. And that’s the homocommunist way when, you know just put it on a shirt!

JC: Maybe it’s like porn: We’ll know it when we see it.

AS: I mean I also think some essential homocommunist imagery are related to like the Black Panther history because we have homocommunist icon, Angela Davis and Huey Newton, who also was a fighter for queer and women’s rights. Those are essential as well and speak to the intersectionality and the interconnectedness of our oppressions and our fight for liberation and solidarity.

JC: The answer will come to us in a wet dream.

AS: We will be awaiting in anticipation. That is queerness and that is communism. It’s always an anticipation of what is to come.

Viva la gay revolution, wicked pisser!

Images in the magazine from @Homocommunist archive.

Andreas Fux, 1992.

“Always together!”USSR, 1958. / Ink Magazine no. 23, 3 December 1971.

Rosa von Praunheim, “It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives,” 1971. / Antihomophobe Action c. 2007.

Jürgen Wittdorf, “Friendship Photo,” 1964, East Germany.

Linda Simpson, “My Comrade,” 1987.

∩

\\

/ )

⊂\_/ ̄ ̄ ̄ /

\_/ ° ͜ʖ ° (

) /⌒\

/ ___/ ⌒\⊃

( /

\\

U